Wherein I manage to answer every question with a No, I don't have one of these, but how about this tangentially related answer? (Via

![[personal profile]](https://www.dreamwidth.org/img/silk/identity/user.png) sovay

sovay and

![[personal profile]](https://www.dreamwidth.org/img/silk/identity/user.png) osprey_archer

osprey_archer)

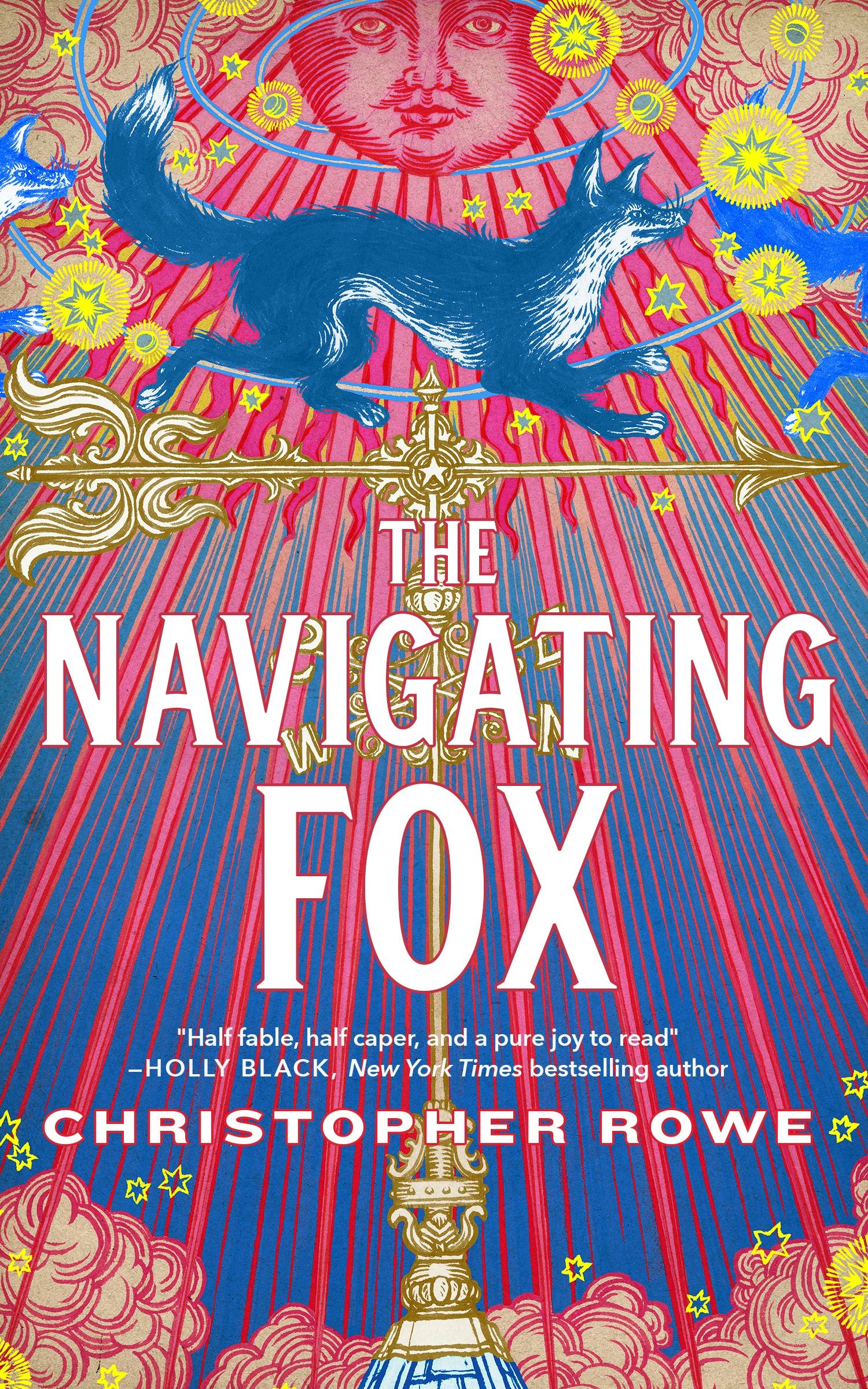

1. Lust, books I want to read for their cover.

There aren't any of these right now, but back when I was a kid, I picked up Patricia McKillup's

The Forgotten Beasts of Eld because of

this cover. I loved the evening sunset glow of it, very Maxfield Parrish-esque.

2. Pride, challenging books I finished.

When we're talking about reading for pleasure, I'm pretty much of a quitter when the going gets tough, so I can't really say there are any of these. Maybe reading the Portuguese version of

Ideas to Postpone the End of the World (

Ideias para apiar o fim do mundo), but see, then it's not entirely pleasure reading; it's partly language practice. And it's a very short book, so...

There are books that have lingered in my currently-reading pile pretty much untouched, and it's not that they're super challenging, they just take more commitment than I can often muster, e.g., Elinor Ostrom's

Governing the Commons, which I want to read for the information, and it's engagingly written, just .... for

pleasure I'd rather read other stuff.

3. Gluttony, books I've read more than once.

I did this a LOT as a kid, but I haven't as an adult (except for, e.g., reading childhood faves to my own kids). Instead what I do is reread particular sections or passages that I love, but honestly, I don't even do that very often; mostly it happens when I want to share something with someone. This happened recently with Susanna Clarke's

Piranesi, for example.

4. Sloth, books that have been longest on my to-read list.

I put things on my to-read list with thoughtless abandon; I don't even know what-all is on my list, and often they're things I'm only vaguely curious about. A bigger sign of sloth is the books I start and don't finish, like

Governing the Commons, noted above. Or Robin Wall Kimmerer's

Braiding Sweetgrass, which I think is beautiful in its moment-by-moment observations (some of which jump vividly to mind when I type this), but which, overall, I have a terrible time sitting down to read.

5. Greed, books I own multiple editions of.

I only own multiple editions of stuff I used when I was teaching in the jail, and I've been thinning those out (but e.g., I had multiple editions of Esmeralda Santiago's

When I was Puerto Rican).

6. Wrath, books I despised.

Books I take a deep hate to I generally don't finish, but there are books that ticked me off mightily in some aspect or other, even if I didn't overall despise them. The focus on the technology of writing as a sign of cultural advancement that was present in Ray Nayler's

The Mountain in the Sea annoyed me big time, though there were other elements in the book that I thought were very cool, very thoughtful. I have an outsized, probably unfair dislike of

A Psalm for the Wild-Built, by Becky Chambers, very it's-not-you-it's-me thing (

except that the dislike is large enough that I find myself whispering, But maybe it's a little bit you, actually)

7. Envy, books I want to live in.

I don't want to live in any books right now.

As a kid, I tried to get to lots of fantasy lands (the ol' walk-into-a-closet thing, because as an American kid I didn't even properly know what a wardrobe was: in our house, winter coats were in a closet), and I played that I was part of lots of others. But probably the ones I wanted to live in most were Zilpha Keatley Snyder's Greensky books. I wanted to glide from bough to bough of giant trees with the aid of a shuba and low gravity, have a life full of songs and dancing to defuse personal tensions, not to mention psychic powers and an overall jungle environment.