progress!

Jun. 3rd, 2025 12:36 pmI only have three more living room boxes--at least two of which are plushies and fragile things--to unpack. Then I need to organize the stuff that is just sitting around in there and try to find places to put it away. And then organize the closets; in the initial stages of moving, when there was no furniture here to speak of, I just shoved things into closets willy-nilly. Oh, and reorganize the beads and unpack the other box and a half. That won't take long, unless of course I decide to actually organize the huge heap of beads that I bought and never sorted. And I need to put up three curtain rods and their curtains, which means finding several days when neither my legs nor my head are wobbly.

I figure all of the above should be done by the end of June. Then I can start on the sewing room! That's only about forty boxes--a snap, right?

Moving the laundry upstairs is nearly done, too. The plumbing and electrical work are both finished; the electrician was here this morning. So the only thing left is for the new machines to be delivered, next Wednesday. I had planned to use the existing machines, which are quite new still. But installing a vent in the guest room would be Difficult and thus Expensive. So I bought a ventless dryer. And decided to spring for the matching washer, because they're stackable, which will save some room. The whole thing turned out to be three times as expensive as I had figured--the plumbing alone was twice my estimate--but it's very worth it. Hauling laundry up and down the basement stairs was killing me.

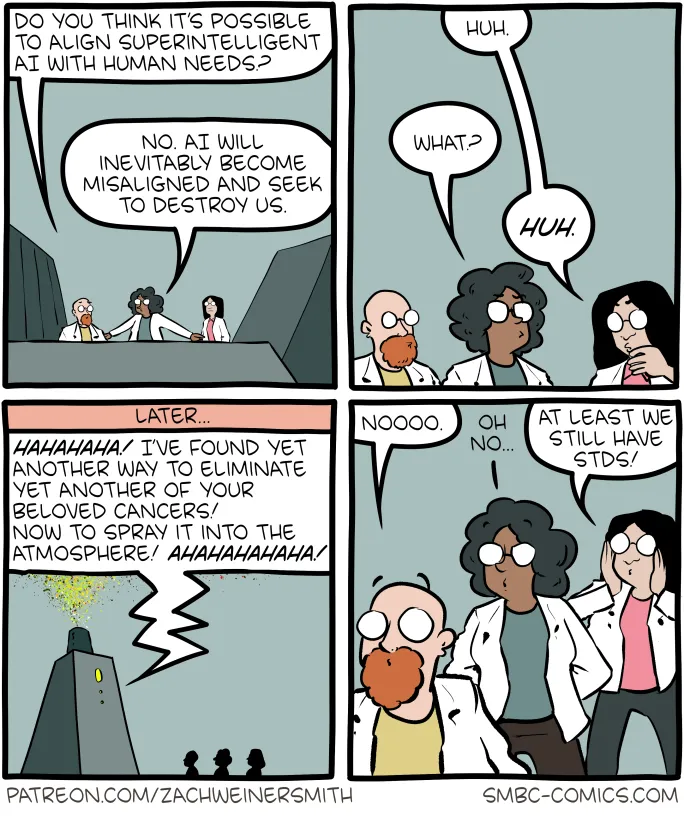

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Evil

Jun. 3rd, 2025 12:34 pm

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

It's not an AI Control Problem, it's an AI Control Solution!

Today's News:

Life in the North Woods

Jun. 3rd, 2025 12:40 pmThing that adds "fun" to the situation, is that one of the trails is the end of the Appalachian Trail, and there will be through-hikers coming out of a long stretch (100 miles) of wilderness to finish off their marathon.

A new home for Dude and Skeeter (and us)!

Jun. 3rd, 2025 12:21 pmtravel-related books and war fiction

Jun. 3rd, 2025 05:38 pmI read this in preparation for our Portsmouth trip, because I know nothing about naval history other than what can be gleaned from watching Hornblower and reading Alistair Maclean. This was a general overview of the 20th century, one book from a twelve-volume history of the Navy, very dense, but surprisingly readable for all that. I never lost interest even when deep in discussion of relations with the navy's one true enemy: Whitehall. Or the other great enemies, Churchill, and the RAF. It was quite clear that the French, Germans and so forth are all incidental to these long-lasting and deep emnities. To be fair, I'll give them Churchill, especially after Gallipoli.

As well as the details of battles and events and so forth, the book somewhat inadvertently told me a lot about the navy's biases and beliefs about itself: the Senior Service, it's known as, and they very much identify with that name. So much outrage at the RAF wanting to be in charge of airplanes, and getting funding that should really all go to the navy because the navy is the true defender of the realm. Which is not entirely false: anyone who wants to get here has to cross the sea, and anyone who wants to get here in large numbers has to cross the sea in boats, and stopping them is very much the navy's reason for existence. And they did it once, spectacularly, defeating the French invasion fleet at Trafalgar, with their great heroic admiral organising the battle brilliantly and dying at the moment of victory, and wow have they spent the next two centuries obsessed by this, clinging to it as a reason for their existence, and trying to find an opportunity to do it again to gain equal glory a second time around. And it was very clear that especially in WW1, this warped their thinking and their planning, which is why their attempt for a repeat at Jutland was, at best, a stalemate, and very far from the glorious triumph they thought was their due - but didn't have the training, strategy or skills to make happen, owing to being heavily mired in the past.

They did learn this lesson by WW2, where they did not attempt to replay Trafalgar, and instead they do their best to claim the triumph of the dog that didn't bark: the argument runs that the real reason the Nazis didn't invade is nothing to do with the RAF's Battle of Britain, but because the Germans didn't want to face the Royal Navy - and it's a fairly strong argument. But their main work in WW2 was grinding, difficult and focused on the economics of war rather than the drama, protecting shipping from U-boats across the Atlantic and in the Mediterranean so that food and the materiel of war could reach the UK at all. And they got pretty good at this after a while, due to throwing lots of effort at the technical and strategic ideas involved. Which was mostly convoy work. There's a whole rather dismaying thing about convoys in both wars: the navy hates convoy work because you sit around and wait to be attacked and it's not dashing and heroic and dramatic at all and you just go very slowly - for a warship - back and forth like a bus driver shepherding a lot of fractious cargo ships until someone attacks you. In WW1 the RN really didn't want to do it even though it was very clear that convoys work amazingly well at protecting merchant shipping compared to letting them go on their own and the navy just wandering around looking for trouble, and it took them a long time to agree to do it. In WW2 they did go straight to convoys, though they had an equally hard time persuading the Americans that they also needed to use convoys once they joined the war; there seems to have been a frustrating period after the US joined in when the RN would escort ships up to American waters and then leave them, and since the Americans didn't convoy them the rest of the way, the U-boats immediately sunk hundreds of merchant ships that had been safely convoyed across the rest of the Atlantic; eventually the US navy agreed to convoy the ships, though it wasn't clear whether they ever agreed to black out coastal settlements (this is important because otherwise the silhouettes of ships are clearly visible against the coastal lights). Anyway, there was that and then the business of getting everyone back into Europe for D-Day and onwards, but again, the navy are obviously a little frustrated that this was clearly the army's moment of glory rather than theirs.

From 1945 onwards, the navy's big enemy has been Whitehall, trying to persuade the government to disgorge enough money to build ships and crew them even though there is nobody particular they're intending to fight, and Redford and Grove make a lot of arguments that you can tell have been made in government offices about how if you want to do anything military anywhere what you need are ships, not airplanes or armies, and so please give the navy more money. Watching the story slowly approach to discussions I hear on the news now, about the point of aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines, was interesting: naturally the navy is always on the side of more ships and more money. An interesting read all around. The funniest bits were where the author interrupts his usual fairly dry style to explain that in this particular operation, everything the navy did was perfect but unfortunately the army/the RAF/Churchill/Whitehall/the Americans/someone else who was definitely not the navy fucked up their part of it so the operation wasn't a success. One of those I'll grant them, but apparently every time an operation involving the navy went wrong it was someone else's fault!

And I also reread The Cruel Sea, which remains THE book for the Battle of the Atlantic and also for adorable levels of shippiness between the captain and first officer of the ship. Every bit as good on a reread, and it was great fun to see models of the Flower class corvettes in the Navy museum after that.

Berlin: Imagine a City, Rory Maclean

I picked this up thinking it was an ordinary history book. It really wasn't, but once I got used to what it was, I enjoyed it a lot. It's a biography of Berlin as told through the fictionalised life stories of a couple of dozen Berliners over time. Unsurprisingly, it's very 20th-century heavy: the book is 400 pages and we get into the 1900s a little past page 100. The individuals who make up the book are mostly real people, though a couple are fictional or semi-fictional (ie people for whom history has left a name and not much else, or people invented as a stand-in to fill a particular category Maclean wants to explore).

The author's presence is quite strong in this book, there are parts that are fictionalised versions of his own Berlin experiences over the years, and the authorial voice and choices and decisions are all very prominent in the book - though oddly there were times when it felt like he was doing himself down. He includes Marlene Dietrich and David Bowie because in various capacities he worked with both of them and was evidently utterly starstruck by both, especially Bowie, and I was not so interested in his hero-worship, if that makes sense; if I'd wanted to find out about David Bowie I'd be somewhere else, I was here wanting this author's voice. His account of Kathe Kollewitz's life was particularly poignant and I am now looking forward very much to seeing her statues in Berlin - though I was moved to tears dozens of times in reading the book, the history of Berlin is the history of horror upon horror and people making their lives in the midst of that. The early chapters in particular did bring home to me just how war-ravaged central Europe was in relatively recent history, compared to the UK; I hadn't actually registered that Napoleon had occupied Berlin, and I also learned a lot about the Prussian kings and Frederick the Great. Absolutely a book to make me even more excited about our upcoming trip.

Olive Bright, Pigeoneer, by Stephanie Graves

The cover of this depicts a young woman, pigeons, a Lancaster and a Spitfire: there was no chance I wouldn't pick it up. It was a frustrating book, alternating between very good bits and rather weak bits and with a heroine whose essential personality was much less defined than any of the other characters'. But I enjoyed reading it anyway, because it had a WW2 setting, spies, a murder mystery and pigeons, so it was not hard to persuade me to like it. Our heroine runs a prize-winning pigeon loft and is hopeful that the National Pigeon Service is going to show up any day now to recruit their pigeons for war work. But instead her pigeons are recruited by the SOE who are training at a nearby stately home. ( spoilers for the plot )

In Love and War, Liz Trenow

A sweet read about three women heading to Ypres in 1919 to find the graves of their loved ones. This was also a bit on the sentimental and predictable side, but fairly well-researched and did a decent job evoking the return to the battlefields and the start of battlefield tourism. The author clearly did her homework about Toc H - complete with an extended cameo from Rev Tubby Clayton - and also about some of the process of identifying graves. And I liked all the main characters and the way their experiences of travel to the battlefields changes them. Workmanlike and well done.

Fannish 50 S3 Post 27: LET THE RUN JIN RECS BEGIN!!

Jun. 3rd, 2025 12:11 pmGiven how well he knows ARMYs, Jin decided to launch a spin-off version titled Run Jin. Across 36 episodes, Jin gets in all types of shenanigans. I'm not going to go thru every eps, just some of my faves.

Gonna start with "Squid Jin-Game"--a take on Squid Game. This time with no gore or death, but plenty of HELLA LULZY moments. The standout in these two episodes is Dongpyo, a 22-y.o. idol who was in X1 and Mirae. He's since gone solo. I love his dynamic with Jin.

Vaguely connected things

Jun. 3rd, 2025 04:54 pmWomen's higher education in London dates from the late 1840s, with the foundation of Bedford College by the Unitarian benefactor, Elisabeth Jesser Reid. Bedford was initially a teaching institution independent of the University of London, which was itself an examining institution, established in 1836. Over the next three decades, London University examinations were available only to male students.

Demands for women to sit examinations (and receive degrees) increased in the 1860s. After initial resistance a compromise was reached.

In August 1868 the University announced that female students aged 17 or over would be admitted to the University to sit a new kind of assessment: the 'General Examination for Women'.

***

Sexism in science: 7 women whose trailblazing work shattered stereotypes. Yeah, we note that this was over 100 years since the ladies sitting the University of London exams, and passing.

***

A couple of recent contributions from Campop about employment issues in the past:

Who was self-employed in the past?:

It is often assumed that industrial Britain, with its large factories and mines employing thousands of people, left little space for individuals running their own businesses. But not everyone was employed as a worker for others. Some exercised a level of agency operating on their own as business proprietors, even if they were also often very constrained.

Over most of the second half of the 19th century as industrialisation accelerated, the self-employed remained a significant proportion of the population – about 15 percent of the total economically active. It was only in the mid-20th century that the proportion plummeted to around eight percent.

and

Home Duties in the 1921 Census:

What women in ‘home duties’ were precisely engaged in still remains a mystery, reflecting the regular obstruction of women’s everyday activity from the record across history. For some, surely ‘home duties’ reflected hard physical labour (particularly in washing), as well as hours of childcare exceeding the length of the factory day. For others, particularly the aspirational bourgeois, the activities of “home duties” involved little actual housework. 5.1 percent of wives in home duties had servants to assist them, a rate which doubled for clerks’ wives to 11.7 percent. For them, household “work” involved little physical action. Though this may have given some of these women the opportunity to spend their hours in cultural activities or socialising, for others it possibly reflected crushing boredom.

Though I wonder to what extent these women were doing something, more informally, that would be invisible to the census and formal measures generally that contributed to the household economy - I'm thinking of the neighbour in my childhood who cut hair at home - ads in interwar women's mags for various money-making home-based schemes - writers one has heard whose sales were a significant factor in the overall family income - etc

***

And on informal contributions, Beyond Formal and Informal: Giving Back Political Agency to Female Diplomats in Early Nineteenth Century Europe:

[H]istorians such as Jeroen Duindam show that there were never explicitly separate spheres for men and women when working for the state in the early nineteenth-century. Drawing a line separating ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ diplomats in the early nineteenth-century, simply based on their gender alone, does not do these women justice.

***

And I am very happy to see this receiving recognition, though how far has something which got reprinted after 30 years be considered languishing in obscurity, huh? as opposed to having created a persistent fanbase: A Matter of Oaths – Helen Wright.

L’Osteria della Trippa in Rome, Italy

Jun. 3rd, 2025 12:00 pm

Although it was recently awarded a Michelin Bib Gourmand, L’Osteria della Trippa still remains under the radar of most tourists toting their lists of usual suspects. At the helm of this cozy tripe-centric spot deep in Trastevere with wooden tables and mustard-hued walls, is feisty chef-owner, signora Alessandra Ruggeri. Here she urges her customers to try, say, a fruity red Cesanese from Lazio along with a daily special of snails stewed with tomato, chiles, and sage.

A self-taught cook who left another profession to open her restaurant in 2019, Ruggeri draws on the flavors she grew up with in Lazio’s Viterbo region north of the capital. “Not only tripe!” she’s the first to insist, but also such cucina povera regional staples as zuppa di pane, a hearty, soupy first course of curly chicory cooked until tender with bread and potatoes, then garnished with grated hard boiled egg.

The quinto quarto selection here is almost encyclopedic, ranging from several tripe preparations— crisp-fried, stewed alla romana, slow-cooked with beans and guanciale—to fried brains, to a stew of pajata (suckling calves intestines) to sauce rigatoni. Ruggeri cooks offal with such a light touch and finesse, even the squeamish will love the surprisingly elegant carpaccio of beef heart marinated in salt, sugar, and spices, and presented in an aromatic puddle of olive oil. Or what might be the city’s best coratella—that’s lamb heart, lungs, and spleen, folks—here cut into dainty cubes and stewed Viterbo style with sweet-tangy red peppers to cut through the richness.

Fratelli Trecca in Rome, Italy

Jun. 3rd, 2025 11:00 am

Unlike the round puffy-edged Neapolitan pies baked in domed wood burning ovens the pizza native to Rome is pizza al taglio: lengthy rectangles or oblongs baked in an iron teglia (pan) in a gas oven, whacked into sections, weighed, and brusquely shoved across worn bakery counters. Under a glistening sheen of tomato sauce or a layer of thin-sliced potatoes? Nice. But just as good is bianca (no topping).

One can find excellent versions at classic spots like Forno Roscioli (good luck getting in) as well as at dozens of neighborhood bakeries. In 2003 visionary pizzaiolo Gabriele Bonci sparked a whole new artisanal pizza al taglio movement at his Pizzarium in the district of Prati, reinventing the genre with sourdough crust, esoteric flours, and cheffy toppings.

One current star among the capital’s new wave pizzerie al taglio is Fratelli Trecca near Circo Massimo, where ancient Romans once raced their chariots. It’s the newest project of Manuel and Nicolo Trecastelli, the talented brothers behind Trattoria Trecca in Ostiense and Pantera Pizza Rustica in Garbatella.

Behind the counter of their cheery new pizzeria with marble tables and soccer-intensive décor are pans of freshly baked rectangles sporting a crust that Manuel Trecastelli has described as “extremely technical.” In fact, it’s downright miraculous: thin and crisp in that Roman scrocchiarella (crackly) tradition, yet sturdy enough to support the weight of the toppings. These come in some two dozen varieties arranged in three categories.

The classiche include bright-red marinara, rosemary-scented potatoes, and seasonal treats like puntarelle with anchovies. Among the ripieni (filled pies) try those with porchetta or slowly braised greens. The speciali meanwhile pay homage to Rome’s quinto quarto tradition: headcheese with artichokes, tongue with puckery salsa verde, or tomatoey tripe.

To drink there are natural wines and craft beers. Still hungry? Try the piatti di giorno like a stew of chicken gizzards with wild mushrooms and onions, plus classic fritti like suppli and fried bacala.

I am never moving to Sweden

Jun. 3rd, 2025 11:40 amShe’s originally from Brazil, but moved to Sweden over a decade ago. We started off talking about general things, like the weather. And she pointed out that it was a beautiful day in Stockholm, but that it was already light out until around 10 pm. Which is crazy. How do you go to sleep when it’s light out that late? And then she told me that in the winter, it gets dark around 2:30 in the afternoon. And I thought Boston was gloomy with it getting dark around 4:00 pm!

I am never moving to Sweden. Their daylight hours are crazy.

Trillion dollars' worth of platinum waiting to be mined on the moon

Jun. 3rd, 2025 09:34 amMilky Way galaxy might not collide with Andromeda after all

Jun. 3rd, 2025 09:13 amQuote of the Day

Jun. 3rd, 2025 11:16 amhttps://futurism.com/ai-models-falling-apart

Heh, cannibalism.

Fancake Theme for June: Female Relationships

Jun. 3rd, 2025 08:07 am

This theme runs for the entire month. If you have any questions, just ask!

This might work

Jun. 3rd, 2025 07:38 amI did watch my friend, Holly, swim laps. Now, Holly is always bitching about the cold even when it isn't. So how in the heck was she swimming in the cold? I realized that while I could be swimming, it would not be fun because of the sun so bike was fine.

I'm now home and it's not yet 8. I'm all sweaty but since I wore yesterday's clothes, I can just step into the shower and then get dressed for the day. I think this will work for a routine - at least until we get volleyball going.

Today is the day the new girl moves in. Her name is on her door and her welcome sign is up. I do no envy her one single bit. My move in day was a nightmare that I do not care to ever revisit.

Today is also house cleaning day. I will probably use that time to make my latest Amazon return.

And more Pride robots/mini monsters. I finished up one last night and changed my mind about how to add the arms. I went to snip off the arm and snipped a hole in the monster. ARUGH. I performed emergency surgery and I think I was able to save him. I'll try new arms today.

But, first a shower.